August 19, 2025

Nicole Suk

Principal, Tax & International Services Co-Leader

Atlanta, GA

Related Services

Related Industries

< Back to Resource Center

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), which passed on July 4, 2025, brought significant change to the treatment of specified research or experimental expenditures (R&E or R&D). Many taxpayers are now able to fully deduct and recognize the tax benefit of research costs when incurred. However, in an effort to promote U.S. business and research, one very crucial element of the tax code was left unchanged.

Background

With the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, beginning after Dec. 31, 2021, specified research or experimental expenditures attributable to domestic and foreign research must be capitalized and amortized ratably over five years and 15 years, respectively. Foreign research is defined as any research conducted outside the United States, Puerto Rico or any U.S. possession. This refers to where the actual service is performed, and not necessarily the location of the entity to which the research cost is being paid.

The OBBB reversed the required capitalization for domestic research effective Jan. 1, 2025. However, the requirement to capitalize foreign research and amortize over 15 years remains in the law.

In addition, it has always been in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 41 that foreign research is not eligible for the federal research tax credit. Many states also have research tax credits that follow this law.

The tax code also states that the abandonment or scrapping of a project does not accelerate a deduction for the unamortized portion of the expenditures, nor does it allow for a reversal of the capitalized amount. Therefore, if the taxpayer scraps a project five years into the 15-year amortization period, they cannot deduct the remaining unamortized costs immediately due to abandonment; amortization must continue as originally scheduled.

Loss of Tax Benefit on Foreign Research

Because of the mismatch in treatment between domestic and foreign research for income tax purposes, the tax benefit for U.S. companies utilizing contractors located within the U.S. may far outweigh those offshore.

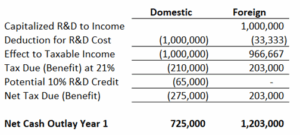

For example, assume a U.S. C-corp (Customer) engages a contractor to perform R&D services, and total annual expected contractor costs are $1 million. If the research contractor is domestic, the Customer would be able to, beginning in 2025, fully deduct the $1 million of contractor costs as eligible research and experimental expenditures as incurred. At a 21 percent federal tax rate, this would result in year one tax savings of $210,000. In addition, the Customer may also be able to claim a Credit for Increasing Research Activities on their corporation income tax return for 65 percent of those contractor costs. For the federal research and development tax credit, contract research expenses are generally taken into account at 65 percent of the amount paid or incurred by the taxpayer to any person other than an employee for qualified research. Generally, the R&D credit is 10 percent of the cost, which may result in additional tax savings of $65,000 in year one. This is a net tax savings of $275,000 in the year in which the cost is incurred.

If the research contractor is foreign, the Customer would be required to fully capitalize the $1 million of costs incurred and amortize over a 15-year period. The costs, regardless of when paid, are treated as placed in service on July 1, thereby resulting in only a half year amortization deduction in year one. In the above example, the taxpayer would be required to capitalize (i.e., add back) $1 million of costs to taxable income and only take a deduction for amortization of $33,333. This results in a net taxable income of $966,667. At a 21 percent federal tax rate, the corresponding tax liability would be $203,000 in year one. In addition, because the contractor is foreign, the Customer would not be eligible for any R&D credits.

In this example, the year one tax difference between engaging a domestic and foreign contractor is $478,000. While over the 15-year period the tax benefit of the research cost is realized whether foreign or domestic, the R&D credit will always only be a domestic benefit.

Taxpayers must consider the time value of money on the cash tax savings of $478,000 in year one. The Customer would recognize a net cash outlay for the contractor expense less taxes of $725,000 under the domestic scenario. Under the foreign scenario, the customer would require $1,203,000 in year one to pay both the contractor and the taxes.

Benefits of Foreign Research

U.S. companies often use foreign outsourced research development for a variety of reasons, particularly to reduce potential costs. Lower labor costs in many countries may result in lower contract expenses; however, costs would have to be significantly lower in order to break even on the tax benefits of using domestic contractors.

Assuming the same example above where the domestic contractor charges $1 million annually, the foreign contractor would have to be at least $65,000 less to make up for the lost R&D tax credit. Even at a reduction in cost to $935,000 the year one tax difference would be $464,805. Over time, although total cost may be less, tax savings would also be less.

Start-Up Companies

Many start-up companies tend to incur losses in the first several years, which may result in net operating loss carryforwards for income tax purposes. In this case, any reported R&D credits may not be able to be utilized for income tax purposes. However, the IRC does allow for start-up companies to claim R&D credits, as claimed on a U.S. income tax return, to offset up to $500,000 per year of payroll taxes for up to five years.

This means that while a taxpayer might not be able to use any R&D credits for income taxes, they will still get the cash benefit by reducing their payroll tax burden. In addition, many states, such as Georgia, have similar rules.

Tariffs, VAT and GST

Most countries do not impose tariffs specifically on research services performed within their borders.

Tariffs are typically levied on imported goods, not services. Research services—like consulting, data analysis, or lab testing—are intangible and usually fall outside traditional customs duties. While direct tariffs on research services are rare, some countries may impose Value-Added Taxes (VAT) or sales taxes on services, which could apply to research.

For example, in 2017 India replaced their indirect tax system, including VAT, with the Goods and Services Tax (GST). While research services provided to foreign clients (like U.S. companies) can qualify as export of services, which are zero-rated under GST, not all services may be eligible for the zero-rate. The current GST rate in India is 18 percent. Any additional GST added to the cost of services would increase the overall cost to the Customer. In the U.S. there would be no sales tax added to research contract expense unless tangible products are being provided.

Utilize Domestic Resources for R&D Expenditures

Companies in the research and development stage tend to be more cash sensitive. Start-up companies look for ways to maximize cash flow in order to fund initial operations. Taking advantage of lower cost contract services abroad may seem like a reasonable route to save cash. However, with the current tax law’s unfavorable treatment of foreign versus domestic R&D, and with the potential loss of any federal and state R&D credits on foreign research, the overall cash impact when taking into account taxes may make it much more cost effective to utilize domestic resources for R&D expenditures going forward.

For questions or more information, contact your Windham Brannon advisor, or reach out to Nicole Suk.